By Prof. William Kolbrener –

I have been sheltering – with Rembrandt.

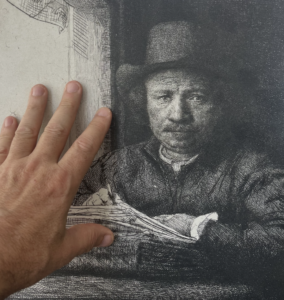

My self-portrait came with Dutch postmarks – inside the parcel, the hemp string knotted, the thick brown paper torn-open, the smooth laser-printed acrylic surface underneath.

Glassy depth and weight.

My portable shelter.

Rembrandt made between 80 and 100 self-portraits. Hamlet has 7 soliloquies. In the Renaissance Age of Discovery, Shakespeare and Rembrandt make a new discovery – the human made in the image of God: the self that creates.

In Act 2, scene 1, Hamlet enters, reading. Some say the book is Montaigne’s Essays, others Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly, many the Bible.

All true: but Hamlet is reading Hamlet. He’s reading the play he is in the process of writing, the story of the self that he is making, becoming.

Rembrandt also creates himself. With stylus on copper plate.

For the 1648 self-portrait, Rembrandt created ten ‘first plates.’ They all look like him. He burnishes and sharpens, soaks in acid, wipes and scrapes. Creating the self requires works and revision. Painting the infinite soul requires more than one take.

Rembrandt’s self-portrait, however, is not a soliloquy. His portraits of the inner world always look outwards.

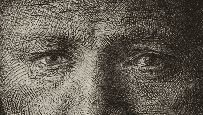

Revelation begins with the eyes, more windows to my soul than to his.

The psychoanalyst, D.W. Winnicott famous for his insights into infant communication, said that it was not that he understood babies, but that babies understood him.

For me, it’s the same with Rembrandt.

The empathic demand of the right eye, the compassionate understanding of the left. Between the two eyes, Hamlet’s ‘mind’s eye’ just visible, and summoning, the ‘human face / Divine,‘ the thrill and burden of revelation.

When I move my head, his eyes follow.

In the epic poem, Milton calls to the muses (and the Holy Spirit). Rembrandt contracts divine inspiration in the light of the forehead and eyes. The ‘likening of spiritual to corporeal forms,’ for Milton a cosmological event, all takes place in Rembrandt’s head. His face illuminates the world on the other side of the window (and not the other way round).

ECCE HOMO

The 1648 self-portrait is the artist’s Ecce Homo: Man made in the image of God: The Human Creator.

The stylus scrapes the copper plate cushioned by layers of cloth beneath it. Or maybe it’s the quill – part of the artist’s hand? – that transmits the light, the pages billowing, breathing their own life.

In the window, Rembrandt shows the two Books that God was said to have authored – the Book of Nature, and the revealed Book, the Bible. The Psalmist David (a favorite subject for Rembrandt) writes: ‘The heavens declare the glory of God.’ There is ‘no speech,’ makes the artist makes them speak. Rembrandt puts his imprint on the book of nature. His signature, blowing in a cosmic wind, gives life to the canvas of the world’s window.

The second of God’s volumes, Rembrandt’s ‘revealed’ Book, is a real book made – look again – from the frame of the window. This book is open, the front page curled up slightly, the pages gathered into the page block against the hard back cover. Rembrandt signs this book as well, open for reading and writing.

The creator emulates the Creator of Genesis: ‘And he breathed in his face breath of life, and the man was a living soul.’

The infinite book has many authors. I want to be among them.

ART FOR DEMOCRACY

Rembrandt paints for a democracy-in-the-making. It’s not just that he fills his canvases with Turks, Persians, Moors, and Jews. But because the impossible task of painting infinity can never be done in a single image, never from a single perspective. Rembrandt paints images that resonate with the divine, but the unseen spirit is visible, and only to the mind’s eye, in the spaces between and beyond them.

Rembrandt’s 1660 self-portrait shows the blood and sweat and pain that the creative self endures. The left eye recedes into a dark socket of oblivion. The right eye, withdrawing still implores, urging courage. But it is the luminous mind’s eye, the not-yet-faded divine image in man, a few brush strokes over the brow, that draws me in.

Somewhere Rembrandt is engraving my image on a copper plate, or dipping me in an acid bath.

From behind the etching in his 1648 workshop, Rembrandt looks at me sternly, impatient (he is sometimes).

But his eyes say:

‘You got this.’

I hear myself saying this.

And I do, and I did.

For the moment, it’s done.

Anyway, I can’t stay in this shelter for ever.

But I take precautions: my Rembrandt is portable.

דיוקן העצמי שלי הגיע עם חותמות דואר הולנדיות – בתוך החבילה, חוט הקנבוס קשור היטב, הנייר החום העבה קרוע, והמשטח האקרילי החלק שהודפס בלייזר נחשף מתחתיו.

עומק ומשקל מזוגגים.

המקלט הנייד שלי.

רמברנדט יצר בין 80 ל-100 דיוקנאות עצמיים. להמלט יש 7 מונולוגים. בעידן התגליות של הרנסנס, שייקספיר ורמברנדט יוצרים תגלית חדשה – האדם שנברא בצלם אלוהים: העצמי היוצר.

בהמלט, מערכה 2, סצנה 1, המלט מופיע על הבמה, קורא. יש האומרים שאת “המסות” של מונטיין. אחרים סבורים שמדובר ב”שבחי הטיפשות” של ארסמוס, ויש הטוענים שזה התנ”ך.

כולם צודקים: המלט קורא את המלט. הוא קורא את המחזה שהוא נמצא בתהליך כתיבתו, את סיפור העצמי שהוא הופך להיות.

רמברנדט גם יוצר את עצמו. עם חרט על לוח נחושת. עבור הדיוקן העצמי מ-1648, רמברנדט הכין עשרה “לוחות ראשוניים”. כולם נראים כמוהו. הוא מלטש ומחדד, טובל בחומצה, מנגב ומגרד. יצירת העצמי דורשת עבודה ורוויזיה. נדרש יותר מניסיון אחד כדי לצייר את הנשמה האינסופית.הדיוקן העצמי של רמברנדט, עם זאת, אינו מונולוג. דיוקנאותיו של רמברנדט את העולם הפנימי תמיד מביטים החוצה.

ההתגלות מתחילה בעיניים. אני לא מסיט את מבטי.

עיניו הם יותר חלון לנשמתי שלי מאשר לנשמתו.

הפסיכואנליטיקאי ד.וו. ויניקוט, הידוע בתובנותיו החודרות לגבי גיל הינקות, אמר שזה לא שהוא הבין תינוקות, אלא שתינוקות הבינו אותו.

עבורי, זה אותו הדבר עם רמברנדט.

הדרישה האמפתית של העין הימנית, ההבנה מלאת החמלה של השמאלית. בין שתי העיניים, עין הדמיון של המלט נראית בקושי, ומזמנת את ה’פנים האנושיות / האלוהיות’. רמברנדט מבין את ההתעלות ואת כובד האחריות של ההתגלות כאחד.

כשאני מזיז את ראשי, עיניו עוקבות אחרי.

בפואמה האפית, מילטון קורא למוזות (ולרוח הקודש). רמברנדט מרכז את ההשראה האלוהית באור שעל המצח והעיניים. ה”השוואה בין רוחניות לצורות גשמיות”, עבור מילטון אירוע קוסמולוגי, כל זה מתרחש בראשו של רמברנדט. פניו מאירות את העולם שמעבר לחלון (ולא להפך).”הנה האיש”

הדיוקן העצמי של 1648 הוא ה”הנה האיש” של האמן: אדם שנברא בצלם אלוהים. האדם כיוצר.

כל הווייתו של רמברנדט, הנפש והגוף, מוקדשים ליצירה.

החרט מגרד את לוח הנחושת המרופד בשכבות של בד מתחתיו. או אולי זו הנוצה – חלק מידו של האמן? – שמעבירה את האור. הדפים מתנפחים, נושמים חיים משל עצמם.

הספר החי של רמברנדט מונח על שולחן, שגם הוא עשוי מספרים. האמן הדגול נשען על ספריהם של אחרים. ספרים על ספרים – ספרים עד אין קץ.

בחלון, רמברנדט מציג את שני הספרים שנאמר כי אלוהים כתב – ספר הטבע והספר הגלוי, התנ”ך. דוד המלך (אחד הנושאים האהובים על רמברנדט) כותב בתהילים: “הַשָּׁמַיִם מְסַפְּרִים כְּבוֹד-אֵל”. למרות שאין בהם “מילים”, האמן גורם להם לדבר. רמברנדט מטביע את חותמו בספר הטבע: חתימתו, מרפרפת ברוח, מעניקה חיים לקנבס של חלון העולם.

האמן יכול ‘לחסום’ אזורים בלוח על ידי החלת שכבת כיסוי נוספת במהלך תהליך החריטה, המאפשרת לחלקים מסוימים להיחרט בעומק רב יותר בעוד אחרים נשארים רדודים.

הכרך השני של ספריו של אלוהים, ה”ספר הגלוי” של רמברנדט, הוא ספר אמיתי שנוצר – הביטו שוב – ממסגרת החלון. ספר זה פתוח, העמוד הקדמי מקופל מעט, הדפים נאספים יחד נגד הכריכה הקשה. רמברנדט חותם גם על ספר זה, הפתוח לקריאה ולכתיבה.

המשטח של הלוח מנוקה, משאיר דיו רק בקווים החרוטים.

הספר הפתוח של רמברנדט אינו מחליף את ספרו האינסופי של אלוהים, ממנו רמברנדט מצייר שוב ושוב. היוצר מחקה את היוצר: הוא חורט, הוא מעורר השראה.

לספר האינסופי יש מחברים רבים: אני רוצה להיות אחד מהם.אומנות לדמוקרטיה

רמברנדט מצייר עבור דמוקרטיה-בהתהוות. הוא לא ממלא את הקנבסים שלו בתורכים, פרסים, מורים ויהודים סתם, ללא סיבה. הוא עושה זאת בגלל שהמשימה הבלתי אפשרית של ציור האינסוף לעולם לא יכולה להתבצע בדימוי יחיד, לעולם לא מפרספקטיבה אחת. רמברנדט מצייר דימויים, כפי שכותב אנתוני ביילי, ‘פיגמנט החתום ברוח’. הרוח הלא-נראית נראית, אך רק לעין הדמיון – במרווחים שבין ומעבר להם.

הלוח עם הדיו נלחץ על נייר לח, מעביר את העיצוב.

הדיוקן העצמי של רמברנדט מ-1660 מראה את הדם, הזיעה והכאב שהעצמי היצירתי סובל. העין השמאלית, שאינה מלאה חמלה כמו בהדפס של 1648, שוקעת בתוך שקע כהה של שכחה. העין הימנית, הנסוגה, מתעקשת, דוחקת באומץ. אך זוהי עין הדמיון הזוהרת, דמות האלוהים שעדיין לא דהתה, כמה משיכות מכחול מעל המצח, שמושכת אותי פנימה.

אי שם רמברנדט חורט את דמותי על לוח נחושת, או טובל אותי באמבט חומצה.

מאחורי החריטה בסטודיו של רמברנדט ב-1648, רמברנדט מביט בי בקשיחות, חסר סבלנות (כפי שהוא אכן לפעמים ).

אך עיניו אומרות:

“אתה יכול לעשות את זה.”

אני שומע את עצמי אומר זאת.

ואני אומר את זה כפי שכבר אמרתי בעבר.

לרגע, זה נאמר.

בכל מקרה, אני לא יכול להישאר במקלט הזה לנצח.

אבל אני נוקט אמצעי זהירות: הרמברנדט שלי הוא נייד.

Translated by Michael Ben Haim.